There’s a good deal more to the crack in the Liberty Bell than my mind has absorbed in its 78 years on this planet.

And, as is usually the case, what prompted this foray into the facts was a recent visit and a photo. The  occasion was a road trip in March with daughter Jennifer. The ride from Connecticut to Florida included a brief, rainy stop in Philadelphia, home of the bell of course. It was the only thing I cared to see there.

occasion was a road trip in March with daughter Jennifer. The ride from Connecticut to Florida included a brief, rainy stop in Philadelphia, home of the bell of course. It was the only thing I cared to see there.

I don’t recall anything specific in school about the crack in the bell. In my mind the bell is a symbol of liberty and over the years it developed a crack, period. The reality is a lot more interesting than that.

One account that made it into the consciousness of most folks, and indeed even into popular media and school history texts, is that the crack occurred when the bell was rung on July 4, 1776, to celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

The fact that the announcement of the signing wasn’t made until four days later, July 8, didn’t stop the myth from grabbing hold. Nor did the fact that this tale did not originate until about 75 years AFTER the signing of the document. Nor even did the fact that the bell wasn’t even in Philadelphia in 1776.

But why let the facts get in the way of a good story, right? And this is indeed a good one.

It starts with a Philadelphia newspaperman named George Lippard, who specialized in what he called “historical fictions and legends,” which he defined as “history in its details and delicate tints, with the bloom and dew yet fresh upon it, yet told to us, in the language of passion, of poetry, of home!”

Philadelphia newspaperman named George Lippard, who specialized in what he called “historical fictions and legends,” which he defined as “history in its details and delicate tints, with the bloom and dew yet fresh upon it, yet told to us, in the language of passion, of poetry, of home!”

Lippard’s 1847 short story, “Fourth of July 1776,” depicts an aged bellman on July 4, 1776, sitting morosely by the bell, fearing that Congress would not have the courage to declare independence. At the most dramatic moment, a young boy appears with instructions for the old man: to ring the bell.

I must also add that this same story introduced an unidentified “tall slender man… dressed in a dark robe” whose stirring speech inspired the faint-hearted members of the Second Continental Congress to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Why note that? Because in a commencement address at Eureka College in 1957, President Ronald Reagan quoted from “historical fiction” writer Lippard in talking about how a speech by an anonymous delegate was the final motivation that spurred delegates to sign the Declaration in 1776. Similar in my mind to Justice Samuel Alito calling upon the debunked theories of jurist and marital rape supporter Sir Matthew Hale in the recently leaked draft opinion on Roe V Wade.

The myths and false narratives just keep on giving, don’t they? Dredging them up to reinforce one’s beliefs seems to have become a popular pastime.

But let’s get back to reality…

The bell was delivered in 1752, ordered up from what is today Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London to replace the one that had been used for alerts and proclamations in Philadelphia since the city’s founding in 1682.

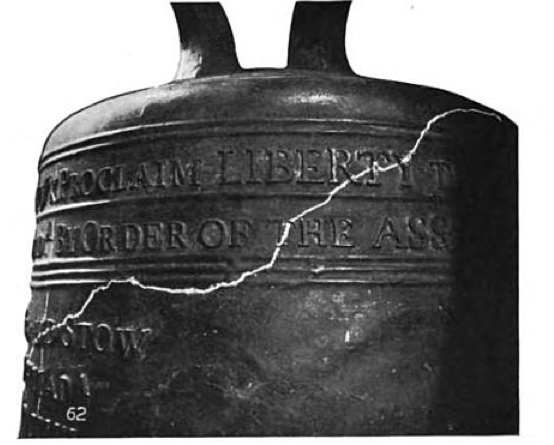

At the initial test strike of the clapper, the rim cracked. Not an auspicious beginning. Two men from the Mount Holly Iron Foundry in New Jersey offered to recast it, and they did, melting it down and adding some copper to the mix to reduce brittleness.

The newly recast bell was unveiled in March of 1753. It didn’t break, fortunately, but the sound was awful. John Pass and John Stow, the two workers from Mount Holly Foundry, quietly melted it down and recast it once again.

The new one was rung later in 1753. The sound was deemed satisfactory, and it was installed in the steeple of the State House.

The bell then entered a pretty mundane phase of life. Not yet famous, it became simply one of many bells around the country used on celebratory occasions, to announce public meetings, and even, for a while, to summon worshippers to services while their own building was under construction. Indeed, in 1772, there were citizen complaints that the bell was rung too frequently.

During the Revolutionary War it spent nearly a year hidden under the floorboards of the Zion German Reformed Church in present-day Allentown during the British occupation of Philadelphia. Returned to the city in 1778, it was in storage for seven years until being hung on an upper floor of the State House.

Are you paying attention to the dates here? This bell wasn’t even in Philadelphia in 1776!

Back in action in 1785, it resumed ringing in the auspicious and the boring. Ownership of it passed from the state to the city of Philadelphia in 1799 with the move of state government to Lancaster.

It was still not famous. Remember, Lippard didn’t write his tale of the aged bellman until 1847, 48 years later.

And there was no crack yet, at least one that anyone noticed. A hairline crack appeared sometime between 1817 and 1846, most likely in the 1840s. The wide, visible and iconic crack that we see today is actually the result of attempts to stabilize the fracture so that the bell could continue to be used. The crack itself continues to the right above the visible crack to the top of the bell,

between 1817 and 1846, most likely in the 1840s. The wide, visible and iconic crack that we see today is actually the result of attempts to stabilize the fracture so that the bell could continue to be used. The crack itself continues to the right above the visible crack to the top of the bell,

It finally was silenced for good in 1846, stilled forever before it even became famous.

As the 1847 Lippard account of the crack grew to be widely accepted, the fame of the bell grew. By 1885, the Liberty Bell was widely recognized as a symbol of freedom, and as a treasured relic of Independence, and was growing still more famous as versions of Lippard’s legend were reprinted in history tomes and schoolbooks. It was on tour seven times from 1885 to 1915, traveling by train and making numerous viewing stops. After coming back from a Chicago trip with a new crack, further trip proposals were met with greater opposition. Philadelphia allowed a final trip, to San Francisco, in 1915, and refused further tour requests.

It lost one percent of its weight during its touring days, much of it to the bell’s private watchman, who had been cutting off small pieces for souvenirs.

One final Liberty Bell note. The second US human space flight in 1961 was in a Gus Grissom-piloted Mercury capsule dubbed Liberty Bell 7. The bell-shaped craft even carried a painted-on replica of the famed crack. Coincidentally, the mission developed a “crack” of its own: A prematurely opening hatch on splashdown put Grissom in danger. He got out, but the craft sank three miles to the bottom of the ocean, not to be recovered until 1999.

I don’t believe a word of this. I do hope the weather in CT is as glorious as it is up here. Leslie

LikeLike

Still a bit too cool for me. Glad you made it up there OK.

LikeLike